He defied the Nazis in the concentration camp. He had an unshakable faith in Divine Providence and in his mission.

Enrique Soros

Within the framework of the international celebrations in Chile for the 75th Jubilee of a crucial decision made by Fr. Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement, Exaudi.org has already presented two articles about him. The first one summarizes this concrete act, the causes of his exile, his liberation and the state of his cause for canonization. The second is a living testimony of Patricio Ventura-Juncá, of the two months he lived with Father Kentenich in Milwaukee, which changed his life.

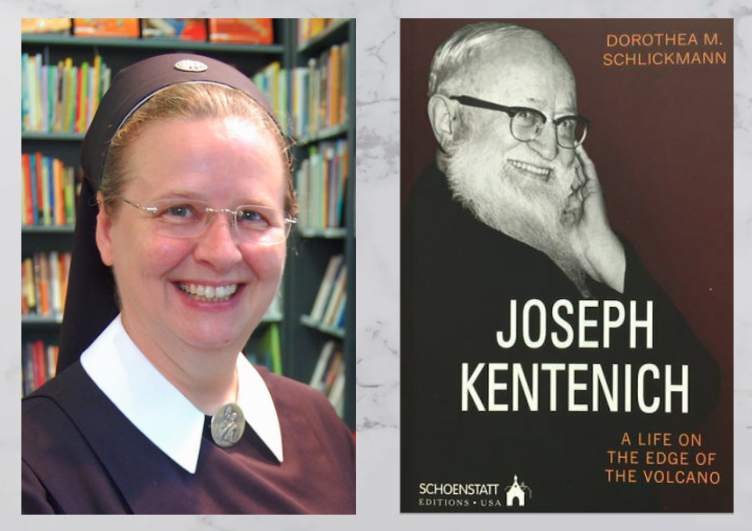

In this third article, we offer through an interview, the vision aboutFr. Kentenich of Dr. Dorothea M. Schlickmann -Sister Doria-, a historian who wrote the book “A life at the foot of the volcano.” As a historian, her method of work is strictly scientific. She affirms that no one has to be Catholic or pious to find the life of this priest and her book, which was published by the prestigious Herder publishing house, interesting. In the course of a year, five editions were published, and the first prints were by no means small.

Sister Doria, you wrote the book “A Life at the foot of the volcano.” It deals with the life of Father Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement. Why did you write it?

In the first place, because I find Father Kentenich’s biography exciting. He lived taking risks. I think of when he was a prisoner of the Nazis in Koblenz. Instead of complying with Nazi orders to glue bags together, he used the paper to write letters secretly and send them clandestinely out of prison. When he arrived at the Dachau concentration camp and the guards mocked the priests, one Nazi told him, “We have never seen God here!” and Fr. Kentenich replied for all to hear, “If you have not seen God here, you have surely seen the devil.” On another day, an SS man treated him aggressively, shouting at him. The next day Fr. Kentenich asked the Nazi calmly at the reception, “Why did you shout at me like that yesterday?”, and the Nazi took him to his office. Everyone thought: Kentenich is going to pay dearly for his audacity. But the Nazi began to talk about his private life, confiding it to Father Kentenich. In my book I describe these and many other incidents where he risked his life.

Kentenich provoked controversy in the Church

From a purely historical point of view, his life passes through some very interesting periods of contemporary history: the imperial era, the First World War with the serious upheavals in Europe, which was passing from a monarchy to democracy, the Weimar Republic, the Nazi regime and its massive persecution (for Fr. Kentenich it meant a month in a dark and tiny bunker, then imprisonment and three years in the Dachau concentration camp), and finally the post-war years with its various facets of reconciliation and new beginnings, until the Second Vatican Council, which marked a turning point in the universal Church.

During this time, Fr. Kentenich was not an observer in a pious corner, but made his voice heard in many ways, directly and indirectly; not least through the founding and expansion of Schoenstatt, a spiritual movement with various forms of community, with a new and original spirituality, which at first provoked controversy in the Church, especially in Germany.

The book helps to discover new paths in the midst of crises

I thought that Fr. Kentenich’s life could reach many people, also those who are in a period of searching. He is not an end in himself, so that members of the Movement or others have someone to be enthusiastic about. Through his life, after all my studies, I felt that he had something to say to all of us. The reception of the book by different readers has reinforced the idea that people from different backgrounds and in extreme situations, by reading it, have felt encouraged and inspired to commit themselves to faith and not to lose hope. For some, it helped them to discover new ways in the midst of crises and, following Father Kentenich’s example, to understand that it is never too late to start again.

It helped many to discover that even experiences of pain, for example in childhood, are not an obstacle, that life can have deep meaning and can become a gift for others. This exemplary character of what faith can do in a person and with a person was very important to me, through the presentation of Fr. Kentenich’s biography.

How did you come up with the name of your book?

The title of the book refers to a quote by Nietzsche, with which this atheist philosopher wants to shake people into daring to take risks, to stand out from the crowd, to show courage, to prove themselves brave. To succeed in paving the way to a higher culture, these kinds of people are needed. “Build your cities by Vesuvius!” is its central imperative. It is worth rethinking the quote at the beginning of my book. According to Nietzsche, he who is afraid to live in the midst of dangers cannot become fruitful.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, whom Father Kentenich often quoted, even though he was banned by the Church for a long time, is considered the mastermind of an epoch in which we live today. His atheistic doctrine of the “superman” was not only very well received by Hitler and the Nazis, but increasingly characterized our whole world: to live as if God did not exist. (Nietzsche: “God is dead…”). However, Nietzsche pays homage precisely to those people who spared no dangers to defend, live and put his vision into practice.

Doesn’t the title seem exaggerated, living at the foot of a volcano?

If this seems exaggerated, just take a look at the history of the churches. Many believers, especially from the gallery of saints and martyrs, “built their cities on the edge of Vesuvius,” had an oppositional conscience, resisted, also under fascist and dictatorial systems, out of conviction, out of faith. It is precisely those people who are so willing to take risks, that dare to try something new, who are not obsessed with getting it right, who do not offend or harm anyone, who change our world and become enormously fruitful. They make a difference. There are countless examples of this even in professional history, but also in the history of the Church up to the present day. Just if we think of Mother Teresa, Roger Schütz or Pope St. John Paul II. And this is also true for Fr. Kentenich. No, I don’t think it is an exaggeration. On the contrary, I am convinced of what the Bible says: that whoever believes is capable of moving mountains of any kind. It would be an exaggeration if we could not give concrete examples of this.

The background of such a conviction is the fact that faith enables us to be brave and courageous in the first place, that it gives us the strength to think and live differently because a power greater than the purely human one carries us and moves us.

And why do you relate this phrase to Fr. Kentenich?

He took many risks from the very beginning and also took an alternative educational path: the founding of the movement with a handful of boys in the middle of the First World War, most of them at the frontlines. Only ten of the first members of the Marian Congregation came to the famous founding lecture in the chapel on October 18, 1914.

He gave such a programmatic address: that from here, through Mary, a movement of renewal should begin, and go far beyond the borders of Germany. And in the midst of a Germany that was despised during the Second World War, where all non-Germans were regarded as enemies by the regime, he founded the International in Dachau. Evening after evening he gave lectures in Latin in the Polish priests’ block.

He took a risk with a new system of education

He founded the first secular institute – the Sisters of Mary – with a new form of community and without vows, without yet having a legally secure framework for it within the Church.

He did not dictate norms, to immediately submit them to the ecclesiastical authorities, but first let life speak and develop, with the members themselves drafting the first statutes, which they had to put to the test in life.

He entrusted young men with leadership responsibilities, made them independent, and decentralized those who did not want to be Pallottine priests but instead wished to form their own community as diocesan priests.

He made inroads with a completely different way of education that had much of a spirit of risk-taking, because it is based on mutual trust, not on control. When he was not yet a spiritual director and he saw from the gallery of the house chapel how the boys were fighting in the pews while they should have been praying the rosary, he said to himself, “With my method it can’t be worse: I dare to try!”

He risked his person and his Work without hesitation

The risks he took are innumerable, whether one thinks of his willingness to surrender in prison on January 20, 1942, where he renounced a re-examination by the prison doctor, who might have declared him unfit for the concentration camp. This might have saved him from Dachau, but he put everything on one card: God and the holy life of the members. Only through this spiritual commitment did he believe he would be freed.

Also the courageous step of May 31, 1949, the letter that had its beginning in Chile, openly calling the attention of the bishop of Trier to the misunderstandings, the misinterpretations of the Visitor, his good friend, Auxiliary Bishop Stein. In it, he spoke about the weaknesses of the German Church, risking not only to be rejected, but to be silenced altogether. Whoever reads my book will find this spirit of risk in his ideas and actions on practically every page.

In your opinion, what can Father Kentenich’s message be for the people of today, for today’s world?

The question of God remains always topical. Fr. Kentenich can help to shed a new and different light on the subject: If God exists, and He is as Jesus Christ communicated Him to us, then he has something to do with everything we do, think, and feel, with what constitutes our being.

A God in the clouds evaporates

Man cannot live without God. Even a social system based on Christian roots cannot survive without the root. But a God who is only transcendent, who hovers in the clouds, so to speak, far away from me, evaporates over time, as Fr. Kentenich critically points out already from the beginning, for he has no relevance for my life.

Fr. Kentenich is a provocateur, not a quiet person. He aroused and continues to arouse in people a restlessness for God. This is still relevant, the more it seems from the outside that we are all abandoning the faith. His message was always: there is a God who can be experienced personally and who says something to my concrete life. Clearly there is no God that I cannot experience personally.

Believing in a personal God changes everything, also today!

Other important relationships for us come into play in our relationship with God: our relationship with ourselves, with others and with the world. In his original educational contribution of the personal ideal, Fr. Kentenich opens access to a self-reference and self-realization that goes beyond mere state of mind and situational decisions. It gives personal life a profound meaning, and at the same time expresses the uniqueness of each individual person.

Believing in a personal God who is close to me as a loving father changes my relationships: those with my wife, my husband, my children, my friends. It fosters in me an appreciation for others because they are creatures, images and children of God. This leads me to an attention and care not only towards my fellow human beings, towards the nature of man, but also towards creation as a whole, towards the environment that has been entrusted to us and for which we are responsible.

This perspective also opens up a different way of dealing with borderline and painful experiences, relationship problems and self-doubt for people today.

Organic life vs. mechanistic life

Fr. Kentenich often spoke and defended his vision of organic thinking, living and loving. He was convinced that the Church, in adapting to the modern world, was also losing this organicity because it was allowing itself to be influenced by a mechanistic spirituality that separates important inner connections. One may go to church on Sundays, but daily life is spent in a very different manner. People are then dissected into their individual parts without taking into account the inner connections and interplay of forces. The truths of the catechism are understood, but they no longer have anything to do with the personal, inner, even subconscious life of the soul. Idea and life, the natural and the supernatural world, the human and the divine, are separate realms that have little or nothing to do with each other.

This mechanistic spirituality characterizes the human sciences and shapes almost all areas of life that have adapted to the mechanized and digital age. It is expressed most clearly and almost symbolically in medicine when “the liver is in room 1B” and “the lungs are in room 3A.” The human being is divided in such a way that one part no longer knows anything about the other or is no longer integrated in any organic context.

Fr. Kentenich can offer an essential contribution precisely in relation to the ability to think synthetically, integrating various aspects of reality or ideas in order to achieve an organic and coherent synthesis. This is applicable in every field: in family relationships, in business, etc.. This is more connected to the field of psychology and pedagogy, in general with the formation of the personality.

Name three virtues of Fr. Kentenich that touch you the most

His love for the truth, his respect and his capacity to love, which was expressed in his unselfish love for people and in his unreserved love for God.

Fanatic for the truth

I became very aware of his love of truth not only when I researched his so-called youthful struggles, but above all by historically researching his time in exile. Precisely his love of truth created difficulties for him. It was more important to him than diplomacy and brilliant strategies. For him, who described himself as a fanatic of truth, this was not only a precious commodity in theory, but was realized in practice through truthfulness, almost to the point of “self-destruction.” He spared neither himself nor others when it came to truthfulness as an attitude and truth as ethos and ideal.

Because ideas and life went so organically together for him, his own life was permeated with what he believed and recognized as true. He did not say, “Here is the truth and here is my life, sometimes there is a gap, but that is not a bad thing.”

How one can love so much

An academic met him in Milwaukee, and upon returning to Germany, everyone wanted to know about the “real” Fr. Kentenich. They asked him curiously, “So, what’s he like?” His brief answer was, “He is credible.” The same scholar relates that she wrote in her diary after that first meeting, “How can one love people so much (as Fr. Kentenich loved)?”

There is something fascinating in observing to what extent the most diverse people felt welcomed and understood by him, valued and accepted as they were. This was extraordinary in him, especially the fact that he could inwardly affirm the most diverse types of people, without this meaning that he could not also openly and honestly name points of criticism. His love for people was genuine.

Deep respect for the uniqueness of each person

The testimonies insistently express that he was very respectful. He had great respect for the uniqueness of each person, for the mystery that person holds and for his or her life story.

He respected the limits of others, their weaknesses and defects. He had great respect for the treasure of the Church’s faith, the sacraments and the laws of the Church. Some said during the ecclesiastical visitation and during the exile that he had no respect for the authority of the Church. They did not understand that his respect was manifested precisely in his feeling of co-responsibility with the bishops and his high responsibility for the Church.

He could not and should not remain silent in the face of what he recognized as a danger, and yet he was so humble and respectful as to accept all the erroneous decisions and all the injustices that generated his outspoken responses. He never used public means to protest.

Fr. Kentenich took pleasure in originality, in original people, and he also respected those who were rejected by others. His love for humanity was “so human,” “so natural,” “so genuine,” as witnesses repeatedly described it.

He dedicated himself to others without regard for himself, sacrificing himself for others day and night from the very beginning of the Movement. This manifests a love for people of such a degree that, in my opinion, it cannot be explained in purely natural terms.

What does God now want from me, from us?

And this brings us to the question of the intensity of his love for God. His ideal of life was to win people for God in a holistic way. He had experienced God personally, he had experienced what faith is capable of awakening in people, he had experienced how much God loved him personally, concretely through Mary. So many profound experiences of God’s love led him to give a personal response of life, in love.

For him, God and the divine were such a clear reality that he could not help but be constantly attentive to the question: What does God want from me, from us? He was, in the strictest sense of the word, a God-centered person. He is not the only one. Again and again we meet people, especially among the saints of our time, like Padre Pio, for whom God has become an irrefutable reality. Father Kentenich might have had a much easier life if the question of God and his desires had not been so central to him.

This article was originally published by Exaudi.org in English and Spanish on 27 June 2024.

___

Sr. M. Doria (Dorothea) Schlickmann was born in Neuss, Germany, in 1956. She entered the Secular Institute of the Schoenstatt Sisters of Mary in 1978. She studied German, History and Educational Sciences. She received her doctorate from the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Münster with a dissertation on the pedagogy of Father Joseph Kentenich, entitled “The idea of true freedom.” She currently works in the field of historical-biographical research and as an author and educational consultant in the fields of Schoenstatt, ecclesiastical and social work.

TAGS