EXAUDI.org – On May 31, 1949, Fr. Joseph Kentenich placed on the altar of the Shrine of Bellavista, Chile, a letter that would cause extraordinary commotion

Enrique Soros

Enemy number one of the Nazi regime

Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement, was imprisoned by the Nazis for preaching to a third of the German clergy and thousands of educators about the spirituality of an interiorly free and resilient personality, capable of withstanding any type of manipulation. Emphasizing the value of one’s own conscience, this personality remains in harmony with the will of God. This formation took place in retreats that followed, one after the other, in the valley of Schoenstatt, minutes from the Rhine River. Although he did not express it directly, his message was clearly contrary to that of the regime. A free personality was the last thing which Nazism would be interested in. For this reason Kentenich was labeled, in a document generated in Berlin, “enemy number one of the Nazi regime.”

When Fr. Franz Reinisch, a member of the Movement and an enrolled military chaplain, was forced to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler under penalty of death, he asked Fr. Kentenich for his opinion. Should he swear the oath and save his life as many priests had done or should he resist? Fr. Kentenich, consistent with his principles, replied that Reinisch himself should make a decision in conscience, in total freedom as a child of God, without even hinting that one of the options might be the most suitable. Aware of his inner freedom, Reinisch understood that God was inviting him not to take such an oath, a decision which led to his death: beheaded by the guillotine.

His decision of not avoiding the transport to the concentration camp

While imprisoned in Koblenz, the Nazis had decided to send Kentenich to the Dachau concentration camp. Members of the Movement had managed to get the prison doctor to agree to declare him unfit for the camp, because one of his lungs was failing, but it required the express request of the priest to present such a document, and to try to have him exempted from it. On the night of January 20, 1942, after days of prayer and deep discernment, Kentenich consciously decided to do nothing to actively avoid the camp. In Schoenstatt this provoked uneasiness, worry and dismay. The Founder was headed to certain death, and with it, probably also that of the still unfinished Schoenstatt Family. Once again, he lives by the truth that his personal conscience, which relied on the will of God and total confidence in his guidance, is a higher value than any consequence that a decision taken responsibly could entail.

He spent six months in Koblenz prison and three years in the Dachau concentration camp in southern Germany. He suffered terrible living conditions, in which one could barely survive. During this time he dedicated himself to raising the spirits of the priests in his block, and to writing literature, which left the camp illegally, encouraging the Schoenstatt Family to live their radical surrender to the Lord and Mary, trusting in their power, and deepening the ideal of the new person in Christ. In this time of great trials and sacrifices for him and his foundation, the solidarity of destinies between Father Kentenich and his spiritual family grew stronger. Thus he became more aware that, according to God’s plans, the paternal-filial relationship played an essential role in strengthening the surrender and spirituality of his spiritual children.

Living by the spirituality and teaching of harmony between nature and grace

On April 6, 1945, Kentenich was liberated from the concentration camp by American troops. Upon returning to Schoenstatt, he believed that it was an opportune time to share these experiences with the Church. In his anthropological, pedagogical and ecclesial vision, he affirms that in order to aspire to sanctity one should not deny or repress human nature or its creatureliness, as the traditional ideal of sanctity promoted. Instead, like St. Francis de Sales, Kentenich teaches that a healthy attachment to the created order, where God as the Creator is reflected and manifests his will, is the way and protection to reach Him.

It also considers the transcendental importance of natural bonds and human relationships both in the natural family and in a community, and the value of the paternal role in souls as a condition for growing affectively in supernatural bonds and in a profound filial relationship with God the Father, as revealed to us by Jesus Christ in his Gospel.

The human experience of a father and the father-principle

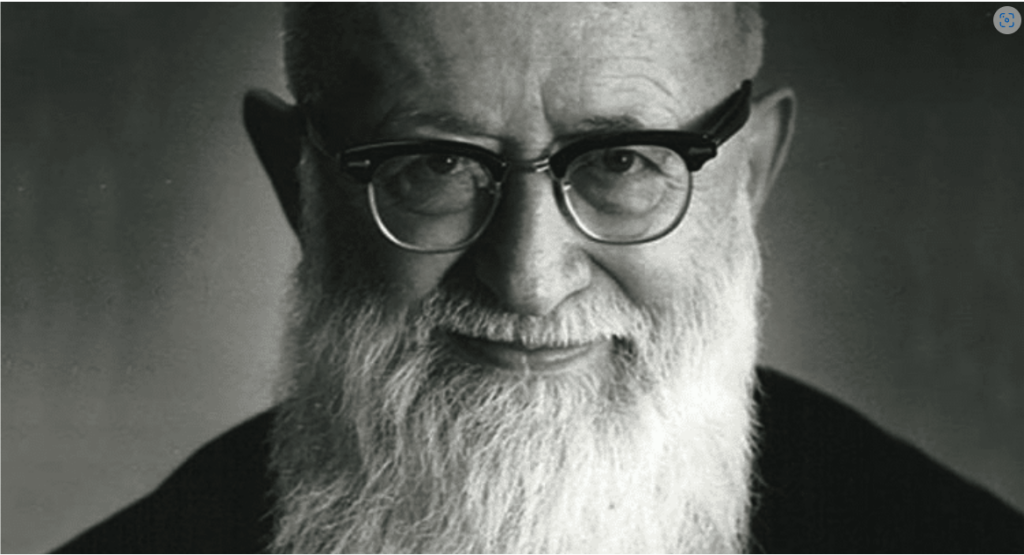

Before Dachau, there are very few photos of Father Kentenich. This is because he avoided being in the foreground and was reluctant to appear visibly as the center and head of the Schoenstatt Work. But when he survived the concentration camp and considered the importance that the attachment to him had for the spiritual growth of his followers, who offered heroic efforts to rescue him, he received clear signs from God, which invited him to assume more decisively his paternity before his spiritual children. It was clear to him that it was not simply a question of being a signpost along the way, but that his mission as founder demanded that he, united in heart with his spiritual family, who aspired to holiness, also be a spiritual father to them and through this living relationship be the way to the heart of God the Father.

Whoever does not experience paternal love on a human level can have serious difficulties in experiencing the love of God the Father. A very clear example of this reality is St. Therese of Lisieux. She had a profound experience of family, and especially an affectionate relationship with her father. This love filled her soul and constituted the strength that enabled her to overcome the hardest trials in the convent of Lisieux: a human paternal love led her to a profound filial experience, which raised her to the heights of holiness, to the love of Christ and his cross, and to the love of God the Father.

Fr. Kentenich was a warm father figure, but also an educator with clear principles. His goal was always to elevate people, integrating all their natural reality towards the supernatural world, towards the heart of God the Father.

Mechanistic thinking and living

In his time, Fr. Kentenich experienced, as we experience even more intensely today in our daily lives, a strong tendency to separate the human from the divine. This has to do with the influence of Protestantism. God is everything, the human being is nothing, only misery and sin; mediations are denied (Mary, the saints, the sacraments…), grace does not penetrate, or simply, God and the supernatural world are absolutely absent and detached from human reality. There is no transcendence and the world is governed only by natural laws and mechanisms.

This way of thinking and living was also rooted in the Catholic Church, to such an extent that even today we still feel traces of it. Importance was given to perfect liturgies, to exact theological definitions, to the formal fulfillment of precepts, norms and rites, but which did not tend to transcend in the daily life of the Catholic population: pomp, but not filial disposition before God; high elevation of the ecclesiastical authorities, but little closeness to the people of God, external compliance, but lack of conversion of heart.

Welcoming the bishop to visit Schoenstatt

After having personally suffered the mechanistic thinking in his youth, he was confronted with the dichotomy he observed in theologians who in their lives did not make transparent the theological truths they preached. When he verified that this way of thinking and living was generalized in the Church, which tended to separate faith and life, Fr. Kentenich understood that after the experiences lived during the Second World War, Schoenstatt was already mature and it was an opportune moment to share these experiences with the ecclesiastical authorities. He invited the bishop of Trier, the diocese in which Schoenstatt is located, to visit the communities of the Movement, to share his vision of a renewed Church from the depths, but especially, starting from that lived experience.

Organic thinking, loving, and living

In Fr. Kentenich’s vision, it is of central importance to unite and integrate all that, in the light of faith, God conceives of as united and integrated: To have a spiritual life not only on Sundays, but it should permeate and animate a way of life, aspiring to a sanctity of daily life. God is present and manifests himself in all aspects of human reality. This is not to be undervalued, but esteemed, embraced, and elevated. This implies cultivating a mentality that, instead of emphasizing the law and formal requirements, which also have their importance, fosters above all a profound and filial relationship with God.

He called the network of relationships and bonds that interweave every human reality with God “an organism of attachments”. These bonds of family, friendship, community experiences, as well as the aspirations of the heart for ideals and noble causes, including the attachment to places and the longing for a personal bond with the God of life that permeates everything, were for Kentenich the hinge on which the human person can rely on in order to draw the strength needed to face the onslaught of the modern world and can live animated by faith, a healthy attachment to God, assuming with realism and positive attitude the challenges of the time. Thus, Kentenich confronts mechanistic thinking and living, which separates in a mechanical way the elements of a whole, with organic thinking, loving and living, which unites everything that God conceives as united.

As far as theology is concerned, organic thinking does not separate Jesus from Mary, but assumes them inseparably united, because by God’s will, Mary’s mission was to bring us to Jesus and lead us to Him. Kentenich affirms that Mary is the surest and most direct way to vitally reach the heart of Jesus Christ. We see here how theology, psychology and pedagogy of God are organically intertwined.

Diocesan Visitation

The bishop of Trier, instead of accepting the request to form a study commission to learn about the contribution that Schoenstatt could make to the Church, sent his auxiliary bishop Bernhard Stein. He proceeded with a canonical –diocesan– visitation, which implied an investigation of the Movement and especially of the community of the Sisters of Mary. This took place between February 19 and 28, 1949. We must keep in mind that Schoenstatt was a young movement (it was founded in 1914), and very new for its time in terms of its spirituality, oriented to the laity and its structure, and that it had a rapid expansion and growth, not only in Germany, but also internationally. The community of the Sisters of Mary, for example, already had some 1,700 members in 1949. But the point was that Kentenich brought innovative ideas that were difficult to understand for a German Church that was very firm in its convictions and tradition, and not very interested in opening up to new ideas.

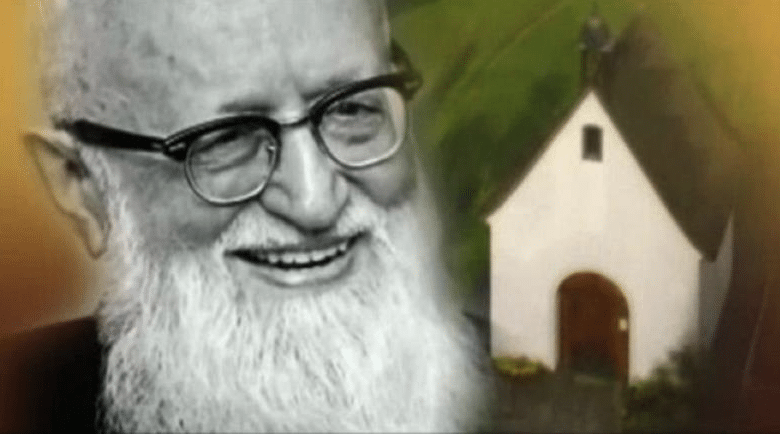

Fr. Kentenich and his followers were convinced of Mary’s presence and action in their little chapel in the Shrine, at the original place in Schoenstatt. They believed that by God’s design, the Blessed Mother had chosen this small place to transform it into a source of graces to form disciples and apostles of Christ for our times. This was assumed and realized through a covenant that the members of the Movement sealed in the Shrine with Jesus and Mary. It is a “Covenant of Love” that strengthens the baptismal covenant and the apostolic character of the Christian. In addition, in Schoenstatt some original terms and expressions were used that were not common in the traditional language of the Church. Although the apostolic strength of the Movement was recognized, these novelties generated distrust in members of the Episcopate.

Visitation Report

Bishop Stein wrote his official report of the canonical Visitation on March 25, 1949, which was sent to Fr. Kentenich on April 27, so that he could take a position on it, in which bishop Stein affirmed Schoenstatt’s orthodoxy in doctrinal and moral matters, including its pedagogical doctrine. But at the same time, he exposes objections regarding some forms and expressions in the pedagogical praxis. He criticizes what he observes a marked dependence and submission of the sisters to the person of Father Kentenich.

The founder received the report while in Nueva Helvecia, Uruguay. He is aware that in some cases there has been this dependence or idealization of his person, but he is also clear that he not only does not support these exaggerations, but feels that his mission consists, precisely, in forming free personalities. His person should stimulate the free persons to move upwards to God, never to become dependent on him.

Kentenich saw that he was not understood. And since the report touched precisely on the core of what he identified as Schoenstatt’s mission, instead of minimizing the fact and letting the criticism pass, he decides to respond to it by expressing, decisively and clearly, what he considers to be an essential theme for the Church is precisely at stake: His vision is that of a new man in the new community; a person anchored in God from the heart, which is made possible and strengthened by the experience of healthy, warm and deep human attachments. He insists, in this sense, on the fundamental importance of the paternal principle, especially in a world devoid, in many cases, of healthy family relationships, which lead to an emotional breakdown due to the lack of a human experience of the father figure, which should be a reflection of the fatherhood of God. In this letter, he exposes the mechanistic thinking, which separates faith and life, the natural and supernatural bonds, which also affects broad circles of the Church, and presents his vision of an organic, integrating world.

May 31, 1949: Risking Schoenstatt’s existence for the sake of the Church’s future

Kentenich was aware that with this letter he risked his own reputation, confronted the hierarchy and put the future of the Schoenstatt Family at stake. He also understood that these principles were a matter of life and death for the destiny of the Church, especially in the West.

He placed the first part of this letter on the altar of the Schoenstatt Shrine in Bellavista, Chile, on May 31, 1949, offering Mary this mutual concern, and trusting that she will glorify herself in it, although he knows that the consequences can be devastating. On that occasion he expresses:

“We have to count on this work wounding deeply noble hearts back in the homeland; that it will arouse violent indignation and cause us to be given strong and harsh counterattacks in response. Let us not wonder if this work arouses a powerful and united common front of influential men against me and the Family. Humanly speaking, we must count, finally, on our attempt to fail utterly. And yet, we cannot be excused from running this risk; he who has a mission must fulfill it even if it leads us into the darkest and deepest abyss, even if it requires one somersault after another!” [1]

Once again, Kentenich risked the future of the Family, being faithful to his conscience and with the conviction that it is God’s will that he does it for the mission that he feels He has entrusted to him.

Later this letter would be known as “Epistola Perlonga” (very long letter), because of its length. It was sent to the bishop of Trier, Franz Rudolf Bornewasser, in response to the report of the Visitation. On a separate, explanatory sheet, he indicated to the bishop that he was only exposing his observations regarding the deterioration of a Christian culture and in the life of the Church in the present time and that he wanted to provoke an objective discussion with which he intended to help the Church to find a more organic way to face the challenges of the time; and that it was not about anything personal against anyone. He presented his ideas with respect and frankness, and as a good German, also with supreme clarity and on a straightforward way.

If he does not leave his Work voluntarily, he would never return

Bishop Bornewasser was sending parts of this Epistle Perlonga to the German bishops, but without including the preliminary explanation. It was to be expected that the bishops did not read it with pleasure. Many of them took it as disrespectful. Let us remember that this was also a time when criticism of the Church was frowned upon. The letter set off alarm bells in the Church. The bishop of Trier requested the intervention of the Holy See, which through the “Supreme Congregation of the Holy Office”, now undertook an apostolic Visitation of Schoenstatt, which resulted as a first measure in the exile of the founder to Milwaukee, USA.

The visitor, Fr. Sebastian Tromp, a Dutch Jesuit, offered Fr. Kentenich two options: If he voluntarily separated himself from his Work, the possibility remained open for him to return in the not too distant future. On the other hand, if he did not do so, the separation would be imposed on him, and he would no longer be able to count on the possibility of returning. Kentenich reflected on it –according to his custom– asking himself what would be the will of God and answered that out of loyalty to his Work and his mission he could not separate himself voluntarily from it, but that he would obey at once if asked by the Church.

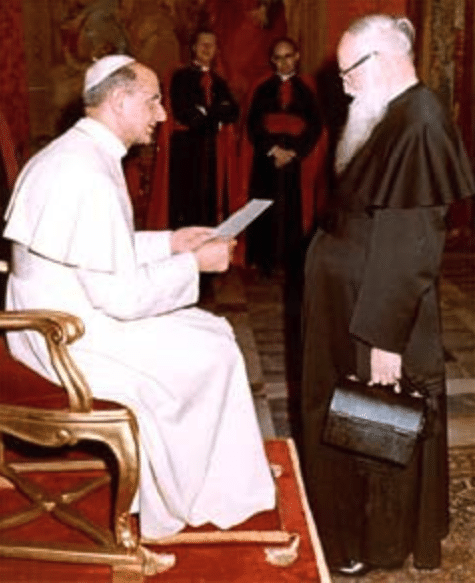

Fourteen years of exile and liberation

Kentenich was never formally accused of any crime and no accusation was ever made against his moral integrity. On repeated occasions he asked the Holy Office to be informed of any accusation and to submit him to an ecclesiastical trial, where he could defend himself formally and present in depth what he envisioned Schoenstatt could contribute to the Church; but this never happened. After 14 years of exile, he regained his freedom after the Second Vatican Council and under the pontificate of Pope Paul VI. Fr. Kentenich was then able to return to Schoenstatt to dedicate the last three years of his life to the communities he founded. He died on September 15, 1968, on the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, immediately after celebrating Mass.

Cardinal Ottaviani: “To err is human, to remain in error is diabolical.”

Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, secretary of the Holy Office, had been responsible for many of the harsh decrees against Fr. Kentenich. After Kentenich’s rehabilitation to his Work, Ottaviani referred to his own attitude saying: “To err is human, but to remain in error is diabolical.” At the end of the exile, Ottaviani even placed a picture of the Our Lady of Schoenstatt in his chapel and on Christmas 1971 he gave the following testimony about Fr. Kentenich:

“All that is left for me to say is about the exemplary value of his humble obedience. He never said or wrote a counter-accusation word or complaint about his painful situation, but he did not conceal his inner certainty that one day the truth would triumph. He knew how to endure, to obey, and to be silent, even to the point of heroism!”

And in a sermon in the chapel of the Holy Office on May 24, 1972, the cardinal stated:

“Although once there were a number of reservations about his Work, a later vision of it has offered much encouragement and confidence. Now we see in Fr. Kentenich’s foundation one of the blessings which heaven has poured out on earth. Let us pray–Fr. Kentenich is certainly in heaven– that he may intercede for us so that we may are granted his virtues: the virtue of humility, with which he mastered in all the vicissitudes of his life; that of obedience, which he lived to the highest degree; that of promptness, which he showed above all in service and by which he sanctified himself and gave others an example of his holiness.”

His Process of Beatification

The cause for the beatification of Fr. Joseph Kentenich has been initiated, although at present in a state of suspense. When the archives of the Holy Office (today the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) were opened in 2020 up to 1958, the period corresponding to the pontificate of Pope Pius XII, the documents related to the exile of Father Kentenich up to 1958 became available for study and research.

While Kentenich was thoroughly investigated during the time of his exile, bishop Stephan Ackermann, head of the diocese of Trier, Germany, where the process in question is being conducted, has also decided that he would not continue to pursue the case until the content of the recent documents published is clarified.

For this reason, he asked that a thorough investigation of Fr. Kentenich’s history, life and conduct continues to be done by independent professional specialists. Trier, then, can make a decision leaving no doubts about the Kentenich case, and be able to resume the process.

The Schoenstatt Movement, for its part, has decided to publish the available documents related to the controversy surrounding the decrees, prohibitions and measures following the visitations and the time of exile against Kentenich and his Work. A series of documents have already been published in a collection of “study editions”, which are available, for now, in Spanish and German. Fr. Eduardo Aguirre, current postulator of the cause of beatification of Joseph Kentenich, is responsible for this work.

What would it be like today for the Church in Germany had they listened to Kentenich?

We don’t know, but as we observe German idiosyncrasy and Church processes, we can ask ourselves what would the German Church be today if the bishops had listened to Fr. Kentenich. At that time it was a rational and legalistic Church, where structure prevailed and there was little sensitivity to new currents of life. Today, the German Church is on the other extreme. Objective values are giving way to subjectivism and emotional takes, strongly echoing the cultural change in the world, where in many cases objective truths are no longer valid and a great deal of relativism is experienced in the face of traditional values. Is this not what Kentenich foresaw if the Church did not react? If the healthy organism of attachments is weakened, the human being loses the meaning of life.

In this sense, Pope Francis is taking the lead today, along the lines offered by Fr. Kentenich, with different charisms and approaches, but with the same goal: Being faithful to the teaching of the Church, to the objective values, giving the Church more human features: authentic attachments, heartfelt, with trust in God’s, seeing God as a Father who accepts our smallness and limitations and with a firm commitment for the destinies of cultures–in covenant with the God of life. The Pope speaks of a “culture of encounter” and of our pressing social responsibility, which would form a large “organism of attachments”.

Jubilee Celebration in Chile

The Schoenstatt Movement is preparing to celebrate, at the Shrine of Bellavista, in Santiago, Chile, the 75th anniversary of the step taken by Father Kentenich on May 31, 1949. This will take place from Friday, May 31 to Sunday, June 2. Registrations are already closed for the participation in person at the historic site, in Bellavista, since the 1,500 registered pilgrims exceed the capacity for the logistics of the event. There will be several celebrations that will accompany the pilgrims in different parts of the world.

More information can be accessed through the following link: https://jubileo31demayo.schoenstatt.cl/

Kentenich’s account of his audience with Pope Paul VI after his liberation from exile:

The Exile and its Conclusion narrated by Fr. Kentenich*

On the occasion of this event, in future issues, we will delve into the mission of the organic vision proposed by Kentenich, and various aspects of his life. His faith in a God who accompanies and guides both the history of humanity and the personal history of each person was so powerfully grounded that he affirmed that a profound filial relationship with God the Father and loyalty to his mission demanded to be able to “live at the foot of Vesuvius” without fear and with fullness of life. This reality deeply and constantly marked his life.

I thank Fr. Eduardo Aguirre, current postulator of the cause of canonization of Fr. Joseph Kentenich, for the critical review of this article.

[1]: Textos Escogidos sobre la Misión del 31 de Mayo, Fr. Joseph Kentenich. Editor: Fr. Rafael Fernández de A. Editorial Nueva Patris.

Taken from EXAUDI.org. Published by Exaudi.org on 11 April 2024.